I went to Berlin with the expectation that my time would be spent serving others. As someone with extensive experience volunteering with vulnerable populations, I’ve come to frame ‘service’ as a form of action. Prior to participating in this foreign study program, I never would have anticipated how valuable simple observation could be in creating positive change. Tangible, sustainable progress must start somewhere, and I’ve come to believe that the first step to success is rooted in a willingness to analyze the trials and tribulations of others with an open mind free of bias. Only then can we hope to borrow from the global community in developing strategies that, if implemented, have the power to improve the quality of life for countless people.

Due to my interest in working with children and families, I was placed with Nürtingen Grundschule as a Community Partner. Nürtingen is a Montessori-style primary school for grades 1-6, and a significant portion of the student demographic comes from migrant backgrounds. They receive state funding and additional support from Kotti e.V., an association that works in close cooperation with the community around Kottbusser Tor to extend vital resources aimed at improving the living conditions of local residents.

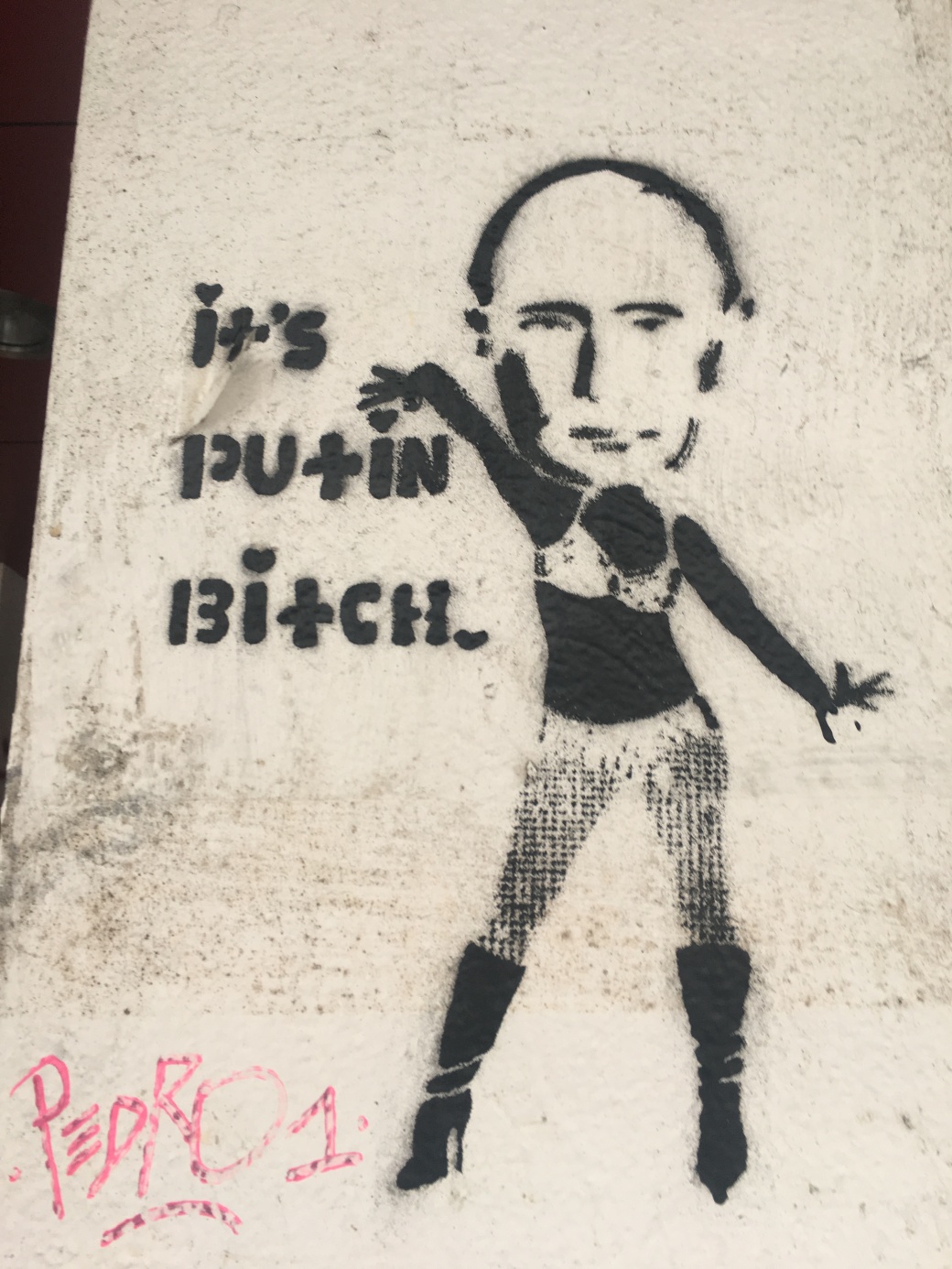

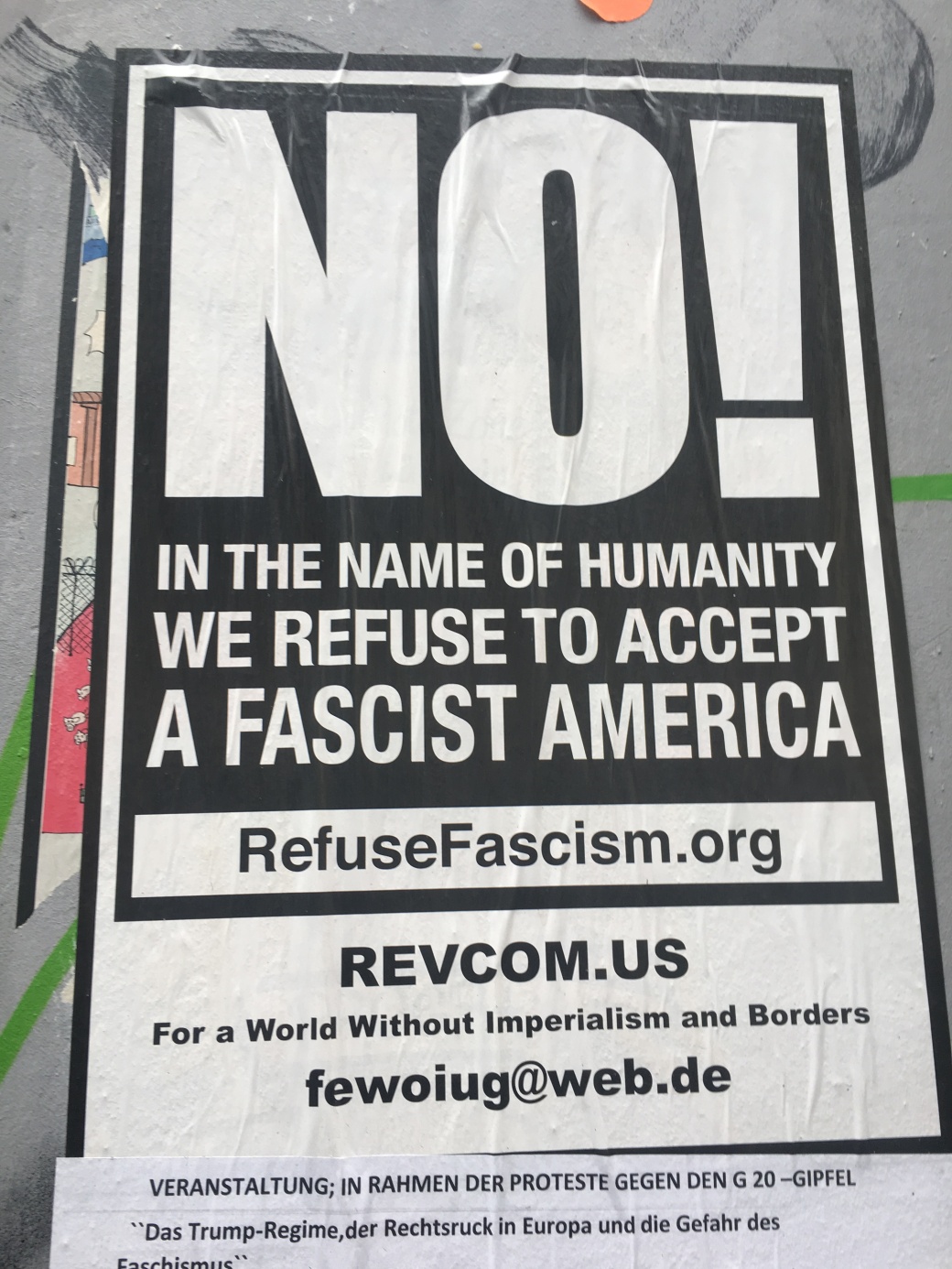

The neighborhood around Kottbusser Tor—lovingly referred to as “Kotti” by the locals—is centrally located within the Kreuzberg district of Berlin. There seems to be a school and/or playground on nearly every block, which says a lot about the value this community places on open access to educational and recreational opportunities for children. One morning I arrived early to my placement and was able to observe parents dropping their kids off for the day; this process was quite different than what I’ve experienced in the US, mainly because in a 30-minute timespan I only saw one student arrive in a car. The rest either walked together in small groups or were escorted on foot or bicycle by an adult. Both residents and staff resoundingly emphasized their strong commitment to ensuring that all children have the opportunity to attend school in the neighborhood they live in, which would absolutely explain such ease of transportation. The community isn’t just invested in the future of their youth, but of all people living in the area. They fight for the right to utilize public space for affordable housing, venues for cultural enrichment, and support systems for those struggling with addiction.

At Nürtingen, special care was taken in designing an environment conducive for facilitating a positive learning environment for children at varying stages of social, psychological, and physical development. The floors and ceilings are acoustically engineered to reduce excess noise, which allows the children a greater degree of freedom to carry out activities without being disruptive to others. Correspondingly, the classrooms do not mimic what we traditionally see in the US; there aren’t rows of front-facing desks focused on one teacher who directs the pupils through highly structured lessons from a whiteboard. Instead, the students participate in arranging the rooms with tables and chairs of differing heights and sizes in a fashion that resonates with them. The teachers aren’t so much ‘running’ the classroom as they are guiding the children through their daily activities, encouraging them to share and work cooperatively. This provides students with an opportunity to explore and learn at their own pace, on their own terms. From what I saw, the priority of the school was not to equip children with the latest technology, but to teach them the kind of social and life skills they need to be successful learners.

The majority of my time at Nürtingen Grundschule was spent shadowing the school social workers. This position seems similar to what we refer to as a ‘guidance counselor’ in the US, but those whom I had the pleasure of observing displayed unmatched dedication and involvement in empowering all students to reach their full potential. Not only do they provide advice and respite during crisis, but also play an active role in developing and implementing programs/procedures that help students mediate conflict independently. They offer of themselves generously, and display genuine engagement in advocating for the well-being of all pupils. I was continuously impressed with their strategies for promoting tolerance and inclusion, and witnessed firsthand how successful they were in earning the admiration and respect of the students, who were in-turn encouraged to respect themselves and one another.

I had the unique opportunity to sit in on a number of administrative meetings, attend conflict resolution workshops with the students, and participate in school activities such as English and cooking classes. My supervisors were extremely accommodating and made outstanding efforts to translate both direct and nuanced information throughout the process. For their kindness and patience, I am indebted to Boris, Ansgar, Anna, Madeleine, and Philipp—this experience could not have been what it was had they not shared with me so freely.

One meeting that I was able to observe was attended by the school headmaster, director of Kotti e.V., lead social worker, and parent of a student. The topic of discussion was how to most appropriately address the challenges that arise at school when young children are fasting for Ramadan. With heavy restrictions on what kids may consume in terms of food and drink, it’s not difficult to imagine that a negative impact would be had on their capacity to perform. Not only could they suffer from an inability to focus on the task at hand, but physical activities and sports could actually be dangerous should one become fatigued or dehydrated. This group had come up with some seemingly fair suggestions for curtailing these concerns that were presented to the Muslim community, and while they gained some support, the biggest mosque in the area declined to accept their revisions. Rather than forcing their agenda–or just giving up–they went back to the drawing board and took a collaborative approach to navigating this challenge within a multi-cultural context. I found this meeting to be especially enlightening because the sensitivity with which the topic was addressed is a prime example of the administration’s dedication to maintaining respectful coexistence within the community.

I was also happy to observe the conflict management training that periodically takes place in every classroom. The children sit in a large circle, and the teacher and social worker will role-play a real conflict that has recently occurred. The children then identify various perspectives of the conflict and together search for a solution. The goal is to teach them how to mediate conflict without resorting to violence or aggression; there is a heavy emphasis on empathy, and the kids are encouraged to speak about their feelings. This program is called “Faustlos”, which translates to an iteration of “fistless”. Interestingly, this curriculum originated in Seattle where it is known as “Second Step” and was developed by the Committee for Children. Grounded in research, the evidence-based program provides students with a common social-emotional language that enables them to be caring, responsible members of society (SEL Curriculum, 2017). The idea is that teaching children to solve problems will promote an environment of safety, well-being, and success both in school and everyday life, and will provide them with the skills necessary to mediate conflict as they grow into adults. Research has shown a range of risk factors (i.e. peer rejection, impulsiveness, inappropriate classroom behavior) can be intervened upon by introducing a curriculum of social skills and school connectedness (SEL Program Research, 2011).

For those students who really struggle to overcome problematic behaviors, the social workers at Nürtingen Grundschule have gone a step further and developed the ISI program (Inclusive Systemic Intervention). ISI was founded upon the desire to allow one little boy to continue attending the school that was located in his neighborhood, instead of allowing him to be funneled into a ‘special’ school for disabled children. The theory is that pupils learn better from pupils, and that they will have a greater chance of experiencing educational success when regularly interacting with peers at different levels of social-emotional development. The goal is to identify children who present risk factors while they are in kindergarten so that grades 1-4 may be spent working with them to develop the skills necessary to be strong learners. It is considered to be of critical importance for the parents to be involved in this process, and such cooperation is mandatory for those in the program. They are given regular updates on their children’s behavior at school (both positive and negative), and are asked to participate in creating goals to be addressed in the home. It took three years for Nürtingen to be approved for the financing to cover the additional six hours of labor that would be dedicated to each child in the program, and at the time the district had never been approached by school administrators who were fighting to continue working with challenging pupils. I found this to be incredibly heroic, and a true testament to the saying, “If there’s a will, there’s a way”.

In the United States, when a child has been labeled as ‘problematic’ they are typically isolated—especially within the public-school system. There are very few opportunities to explore different pathways of learning while still maintaining contact with students who are well-adjusted. By focusing on integration rather than isolation, Nürtingen Grundschule has proven the power of socializing children as ‘normal’. This is evidenced in the growth of those children who would have been cast out as ‘other’s’ as they participate independently in classroom activities, and play nicely with their friends during pause period. When considering the principles that we should be borrowing from to revise our own educational policy, the keywords integration, inclusion, and collaboration come to mind. I’m inspired by the knowledge that one person’s passion can make such a pivotal difference in the lives of so many children, and leave this experience with renewed motivation to be a part of the change I want to see.

SOURCES:

“Introduction to Montessori Method.” American Montessori Society: education that transforms lives. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 July 2017.

“SEL Program Research.” Committee for Children. N.p., 2011. Web. 25 July 2017.

“Social-Emotional Learning Curriculum.” Committee for Children. N.p., 2017. Web. 20 July 2017.

“Willkommen.” Startseite – Kotti e.V. – Aktiv im Kiez. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 July 2017.